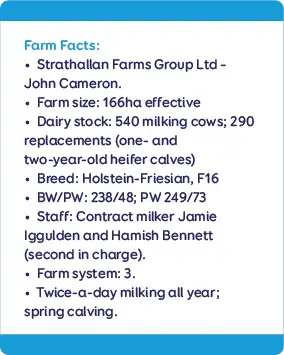

LIC this week revealed that calf No.301 on the Te Puke farm of John Cameron was the co-operative’s 1 millionth dairy animal to be genotyped since state-of-the-art DNA analysis began in the industry in 2008.

Mark Julian, LIC general manager operations and service, said one million was an important milestone for the co-operative. In 2008 LIC was New Zealand’s first dairy genetics supplier to use genomic technology on behalf of its farmers when it genotyped about 5000 sires (historical and active sires at that time), he said.

By 2015 LIC genotyped 35,000 New Zealand dairy animals, the majority of which were cows, Mark said.

These animals also provided phenotypic information, which helped LIC’s research team determine what genes could be associated with good (or poor) breeding and milking performance, including traits other than production. The data helped deliver more accurate breeding values (genomic evaluations) for farmers.

“And with tens of thousands of more calves born this season, that 1 million milestone will continue to be rapidly built upon.”

How do farmers benefit?

Herd improvement, which results in more-efficient cows (conversion of dry matter into milksolids), is coming into sharp focus as industry processors, such as Fonterra, ask farmers to help reach emission-reduction targets. More efficient cows emit less methane per milksolid produced, and calf selection that utilises genotype data is a key tool for herd improvement.

Genotyping, possible through LIC's GeneMark Genomics testing, is a familiar scientific technology among many of New Zealand’s top-performing dairy farmers. Soon after birth, LIC uses genotype information predict how much of a desirable, or undesirable, trait that a calf has inherited from its sire (father) and dam (mother).

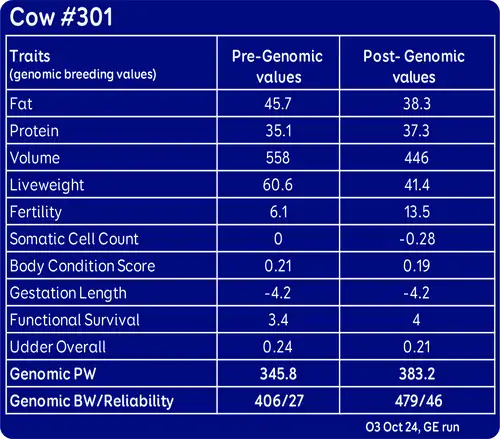

The accumulation of this early trait information allows the farmer to get a more accurate Breeding Worth index earlier for a calf.

This is useful to farmers because it increases their odds of retaining desirable calves for future use in their herd, as older milking cows are replaced by a new generation of emerging heifers.

In turn, this helps farmers fast-track herd performance (i.e., milking and breeding) by using better genetics from one generation to the next (i.e., genetic improvement means that, over time, younger generations of cows will perform better than the previous generation).

Faster, more-reliable, decision making

“Genotyping a young calf essentially provides the farmer with the same information as that of a farmer who’s put their milking heifer through three herd tests,” Mark said.

“The power of genotyping a young calf is that a farmer has essentially the same reliability of information as they would have after a cow’s first milking season; it gives you that information now to make the best breeding decisions for your herd so much earlier.”

Adding value with an eye to the long-term

On the Te Puke farm where the 1 millionth genotyped animal was recently identified by LIC, John Cameron said his motive for identifying complete parentage across his herd, together with DNA-identification of traits within his replacements, was to secure the value of the herd while maintaining a focus on long-term genetic improvement.

“So, for example, when a sharemilker might come on the farm one day, from my perspective, I can have a legitimate herd for sale. The genetics, and the genomic product that sits behind those genetics, will prove how good our asset is within LIC’s (breeding index) system.”

John emphasised that LIC’s GeneMark Genomic product was part of a wider herd improvement picture on-farm.

A key tool in the overall herd improvement picture

About five years ago John told Carly Pool, his LIC Agri Manager, that he wanted his Friesian herd to rank in the top-10% nationally, based on both genomic breeding worth and production worth (gBW and gPW respectively – these are national indexes that rank a cow’s quality and efficiency).

Carly said she helped John map out a plan to speed up the rate of genetic gain of his herd:

“So in 2021 we switched from (Premier Sires) Daughter Proven genetics to Forward Pack so we could take advantage of the latest genomically-selected bulls.

“Then in 2022 we looked at DNA (parentage) to make sure we were actually keeping the correct calves.

“Last year, to really fast-track genetic gain, we pulled out the top-300 cows (based on gBW) in the herd and we started AB’ing (artificially breeding) them using fresh sexed semen.

Sexed semen increases the chances of producing a replacement-quality heifer calf from 50% to at least 90%.

“So the very top cows get the sexed straw (5 per day for 22 days; then 2 per day for 7 days), and the remainder of the top-300 get Forward Pack.”

The balance of the herd got pregnant to natural-mate bulls, but some short gestation length semen Hereford and Dairy was also utilised during the tail-off period.

John’s contract milker, Jamie Iggulden, said the medium-term goal for the herd was to produce an average of 400kg milksolids per cow on the system 3 farm.

That goal was yet to be reached, but it wasn’t far off, Jamie said, and gradual herd improvement was seen as a key vehicle in reaching getting there.

In October mating season got off to a “cracking start”, with the submission rate reaching 85% within the first three weeks.

The herd improvement strategy also involved regular weighing of replacement calves at a nearby grazier’s farm, together with a practice of mating yearlings via artificial breeding to Forward Pack (a mix of genomically-selected bulls and daughter proven bulls).