It’s “critical” to Ray Curtin that he identifies which cows are empty out of the 1400-odd Friesians grazing across his six family* farms.

But he’s “not at all worried” about aging the pregnancies of those in-calf.As far as he’s concerned, the hassle, time, and overall cost of scanning – merely to age hundreds of pregnancies – seems superfluous.

“For me it’s an outdated methodology… I’ve thought for years there’s got to be a better way.”

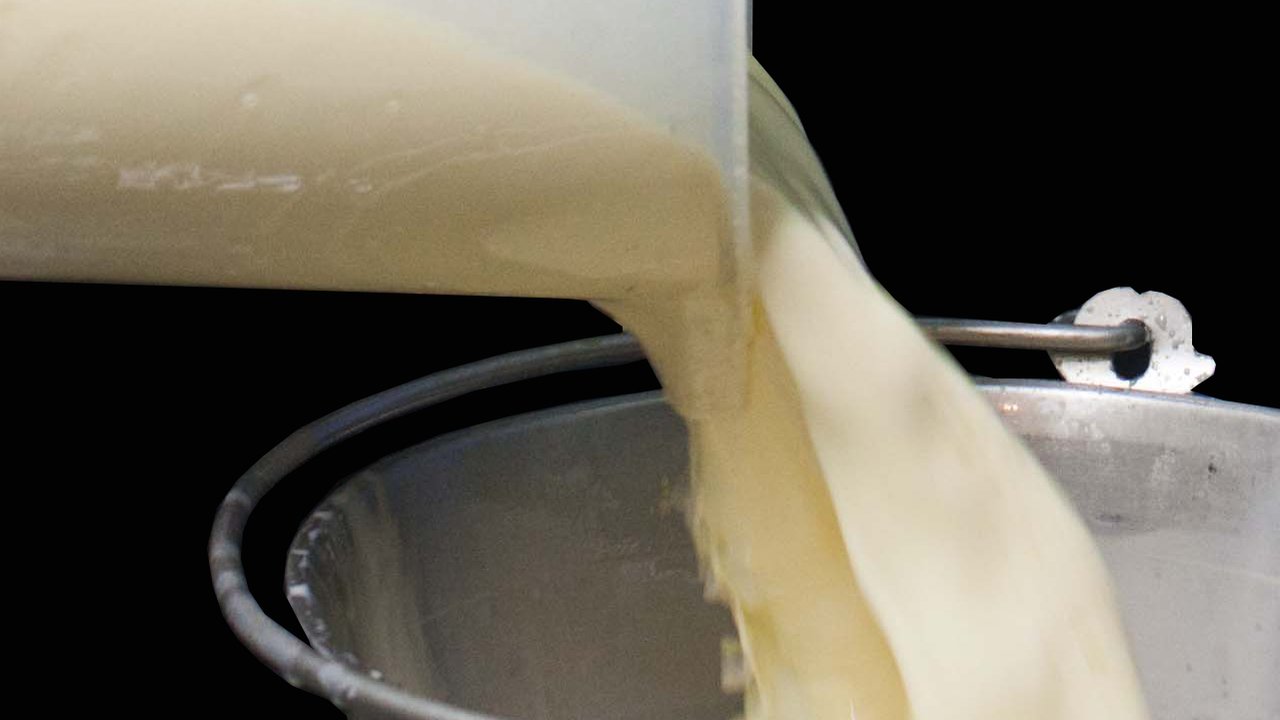

Ray is one of a small but growing number of farmers who are bucking tradition by embracing a new system to distinguish in-calf cows from empty ones: He’s doing this by using the same milk from his herd test samples to test whether his cows are pregnant.

Ray is one of a small but growing number of farmers who are bucking tradition by embracing a new system to distinguish in-calf cows from empty ones: He’s doing this by using the same milk from his herd test samples to test whether his cows are pregnant.

“It’s silent, it’s non-invasive, it’s incredibly accurate, and it doesn’t upset the cow’s routine or her production in the middle of summer.”

Ray is speaking from experience. Next January will mark the fourth time he has undertaken milk pregnancy testing (he was a participant in the first two years of trials, before the solution became commercially available to all farmers in early 2017).

“Yes, it’s true that milk testing doesn’t age the pregnancy, but quite honestly it doesn’t need to… when I’m reaching industry standards, 78% of the herd will be in-calf to AB (artificial breeding) anyway, so those dates are all recorded.

“And, to me, what’s left to the natural mate bull for the final three weeks doesn’t matter.”

Another factor is the ‘flaws of nature’, he says: “Invariably the ultra-scan, or the vet, cannot guarantee a date anyway; it’s no more perfect than aging via a mating date.

“Let’s be honest, discrepancies will happen – just like with human babies, some individuals will be two or three weeks late, others might be a week early. Nature is, at times, imperfect or random at best.”

Ray inseminates most of his cows to Premier Sires with the remainder going to nominated bulls through Alpha.

Once the first six weeks of AB is complete, the easier-calving natural mate Jersey bulls go out for a period of three weeks, with a ratio of one bull to 20 cows.

Like many farmers in his area, Ray was disappointed with an empty rate that varied between 12% and 15% last season – he normally keeps it down to less than 8%.

“But I can’t argue with the accuracy of the milk tests. Of the 30 re-checks recommended after the milk pregnancy tests, the vet’s scan results in April confirmed all but one were indeed empty.”

Katherine McNamara, LIC Diagnostics product specialist, says herd test samples are checked for pregnancy-associated glycoproteins. Glycoproteins are produced by the presence of a placenta, and sufficient levels of these proteins can be used to detect pregnancy from 28 days after conception.

Katherine McNamara, LIC Diagnostics product specialist, says herd test samples are checked for pregnancy-associated glycoproteins. Glycoproteins are produced by the presence of a placenta, and sufficient levels of these proteins can be used to detect pregnancy from 28 days after conception.

The test is therefore appropriate four weeks after a cow’s last known mating date.

The recent induction regulations had triggered the need for a tighter calving pattern for Ray, which is nowadays down to nine weeks. “We’ve got to bite the bullet with calving so we’re completely done by 10 September.”

Several years ago he, along with many farming colleagues, had put the natural mate bulls out until early February – but it was now standard practice to pull the natural mate bulls out well before Christmas (this year by December 15).

Not only does this compact the calving, but it allows plenty of time before the first herd test of the New Year, and is coincidentally an ideal time for the milk pregnancy analysis.

“We get our herd test results and our pregnancy test results all-in-one,” Ray says. “It’s easy, I like the simplicity that milk pregnancy testing offers.”